The Culture of the Church

A Postscript to the Biblical Ecclesiology Study, Part 2

In "Reflections on the Church," I began to call out a fundamental problem: Local churches functioning as social institutions rather than as assemblies of those who follow Christ. This follow-up post explores the cultural implications of this problem, examining how church culture emerges in the context of local churches as social institutions and what this means for our spiritual formation. To get there, I’d like to explore an idea about the source of morals and kick around some models that help me think through the relationship between societies and individuals. Eventually, I’ll try to address how churches as social institutions contribute to this socio-cultural moral formation.

I have long been a proponent of the idea that society sets morals. A couple of memorable, popular Christian books have certainly played parts in shaping this idea: Culture Making by Andy Crouch and Desiring the Kingdom by James K. A. Smith. There are probably many other influences that have convinced me of this, although none more powerfully than my own reflections on the topic of morals. While the simple phrase “society sets morals” causes a room of Christians to pause, ponder and even protest—as their morals come from the Bible, not the secular society—the idea goes deeper than the phrase betrays. Morality is not merely conveyed through society but is a key intersection between philosophy and sociology. This latter point can be reached relatively naturally on the basis of definitions, as the SEP entry on Moral Theory notes in one of its opening lines:

At the most minimal, morality is a set of norms and principles that govern our actions with respect to each other and which are taken to have a special kind of weight or authority (Strawson, 1961).

My question becomes: How? How do societies manage this incredibly powerful trick? Furthermore, how are churches involved in this process, especially if they are social institutions? These questions are rather thick.

Without some notion of the interplay between society and morals, behavioral norms seem ungrounded. “What is the right [thing to do]?” isn’t really a sensible question in the context of a lone individual. Does it matter, really, what a person does in isolation from all others? One might suggest that one’s morals should drive him to survive, to achieve fitness, and to thrive, yet these notions are also ungrounded in the absence of society; we do not reproduce via mitosis. What is fitness without gene propagation? Isolation itself is but a thought experiment, necessarily counterfactual. But I digress.1 At the very least, morality includes the actions of one which involve and affect others, actions done in the context of society, and that’s all that I really need to be true for the sake of this argument.

When compared to the phrase “society sets morals”, this idea that morals are particularly relevant in the context of societies may be taken as the other side of the coin. If morals matter for social living, then one may well posit that society is involved in the creation, setting, or enforcing of those same morals. At this stage, this idea may just be a play on words and nothing more. However, there is certainly more… so much more that it is difficult to choose which branch of the tree to traverse first.

Let us consider the reproductive cycle. Humans, born and unborn, are particularly dependent upon their mother. Those who are not raised, at the cost of extensive sacrifice, are unlikely to survive. Morality is a mother caring for her child, for this is life itself. The process of maturation, no matter how brief, is the very process of learning from others—indeed, one’s mother in particular—actions that are “good”: morality itself. In the case of a wild person, that is, one who has been separated from society at an early age—a maturation process still occurs in that they learn the right way to act from nature itself. The difference lies in merely the “others” from whom the individual learns: is it people or is it the surrounding natural world? Such a maturation sans society clearly leads to uncivilized behavior, behavior that is not appropriate within the context of a society. However, maturation within society necessarily leads to sets of behaviors that the society can at least tolerate and manage. Within the context of a society, a person who is adaptive will find the set of behaviors that leads to their own security and their own being and becoming—their own reproduction, which furthers their own adaptive behaviors through future generations. Such highly adaptable behaviors are precisely those highlighted by society, which naturally attracts human attention; this links these abstract concepts to the much more physical concepts of the mind. Consuming these attention-capturing behaviors encoded in our seniors, songs, and stories is a critical part of the maturation process in society.

Similarly, let us consider everyday life. One must survive, somehow. Normative, exemplary, and maladaptive (perhaps, “immoral”) patterns of survival are put on display for all to see as “entertainment” and further discussed casually through social encounters. While small talk may serve as a way of testing the waters of conversation, it is typical for our opening conversations to include casual discussions about one’s occupation, where one lives, and even what one spends their time doing. As a social relationship grows, how one acquires their food and wares becomes a natural point of conversation, so long as the relationship has progressed sufficiently that both parties are confident that the other will not judge them for these preferences—such judgements being a natural societal corrective mechanism for morals, of course. Thus, it is clear that the vast majority of social interactions and societally-displayed images involve morals: they instruct what is “right” and “good”.

Let us consider death. By the laws of nature, it is final. It is immensely serious; perhaps the most serious thing that may occur in a person’s life, rivaling even their birth. When individuals confront this stark finality, a microcosm of the broader moral framework is put on full display: the funeral scene—necessarily honoring the life of the deceased, commiserating with those who mourn, and remembering the most societally meaningful deeds of the departed. The death of a person within a society is not merely an isolated moment where life ceases but an epicenter for moral reasoning and strengthen the deceased’s society.

This is but a compressed, hand-wavy narrative of how morals relate to societies, but I hope my point is shown. The coin is rightly two-sided in a self-perpetuating cycle of heads and tails: Morals concern societies, and societies set morals.

But how deep does this truth go? Just how much of our being is given to us by society? To what extent is it possible, practical, and good, for one to reject this gift?

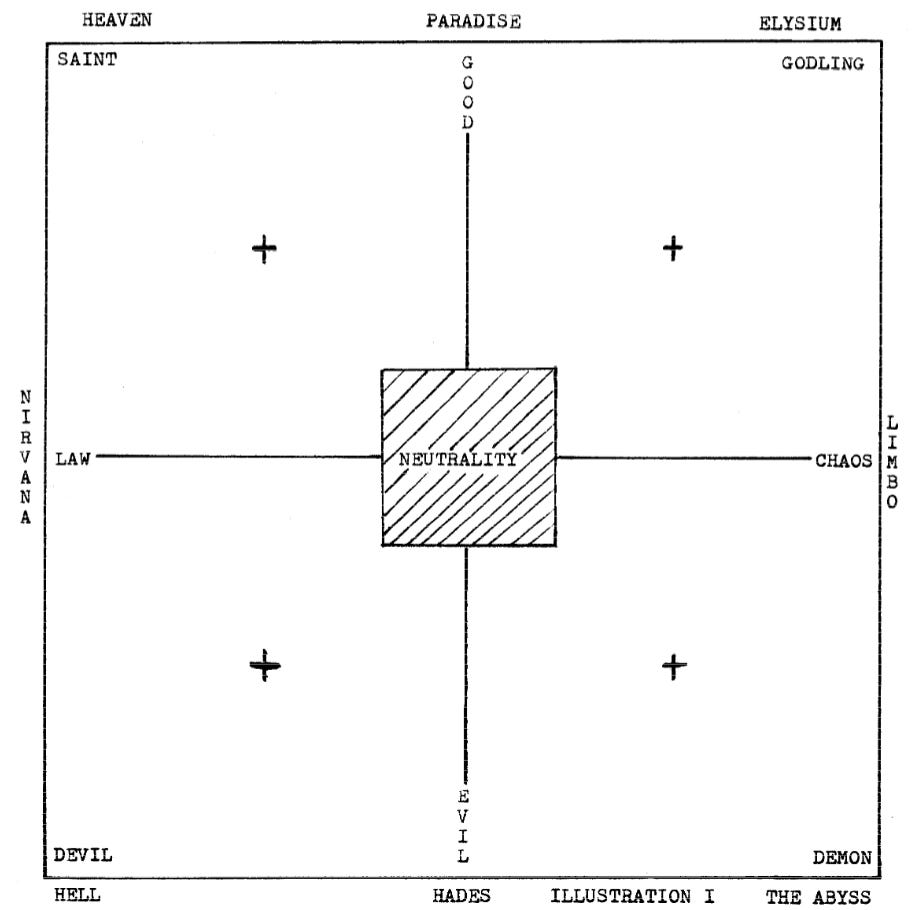

There are two archetypal paradigms that come to mind, each of which offers its own answers to these questions: Order and Chaos. It is no accident that the now-legendary D&D Alignment system features Order and Chaos on one axis and Good and Evil on another. Even today, I find the article on the topic from Gary Gygax in 1976 so compelling that I must digress to share a bit of it with you. He concludes the article with this comment, in reference, of course, to humans in his fantasy world/framework:

As a final note, most of humanity falls into the lawful category, and most of lawful humanity lies near the line between good and evil. With proper leadership the majority will be prone towards lawful/good. Few humans are chaotic, and very few are chaotic and evil.

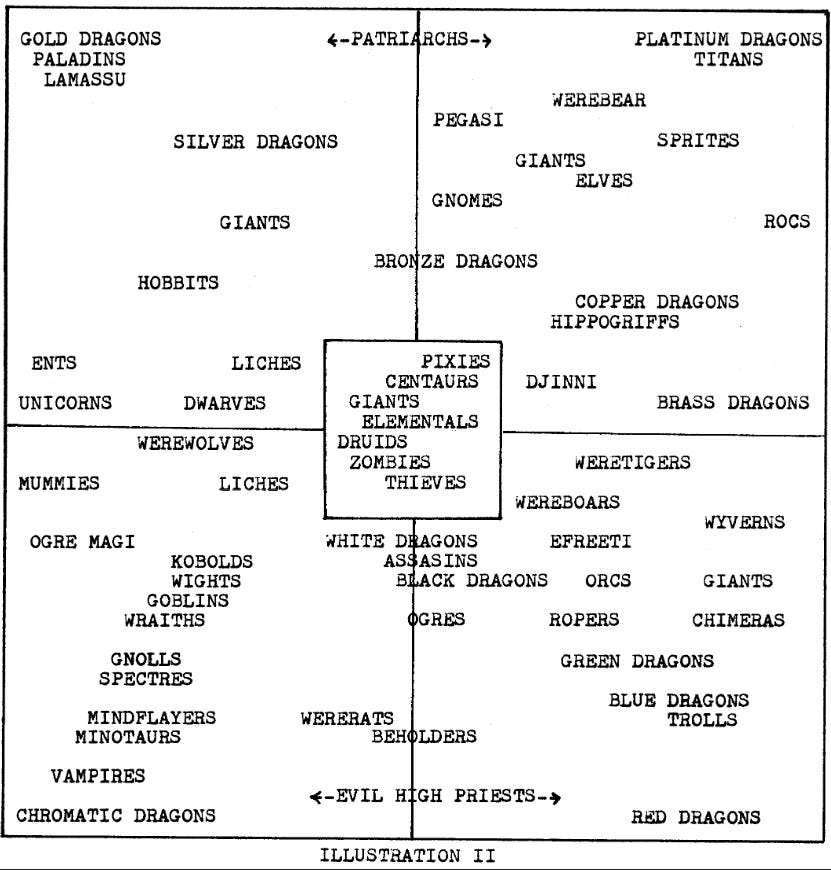

The article concludes with a final illustration, simply showing Paladins in the top right corner, locked securely into LAWFUL, GOOD status. The two images prior to this are quite illustrative. In the first, around the border, we see the places, or “planes”, featured in that early version of D&D, still a core feature in many D&D universes. We also see archetypal “characters” in each corner of the grid.

The precise placement of creatures on this second illustration is hardly of consequence, yet the notion that creatures of different types have default alignments is compelling. Where, pray tell, are you on this grid? Why are you there? Where would you put your society on these axes? Notice one key feature: “Patriarchs”, the heads of families, and in the context of this paper, I dare say, of societies, are fully “Good”, yet they range across the span of the order-chaos axis.2 So, too, it is with society: Creating society is a good thing, but its relationship with order is not set in stone—different societies may be more or less ordered, more or less chaotic, and more or less structured.

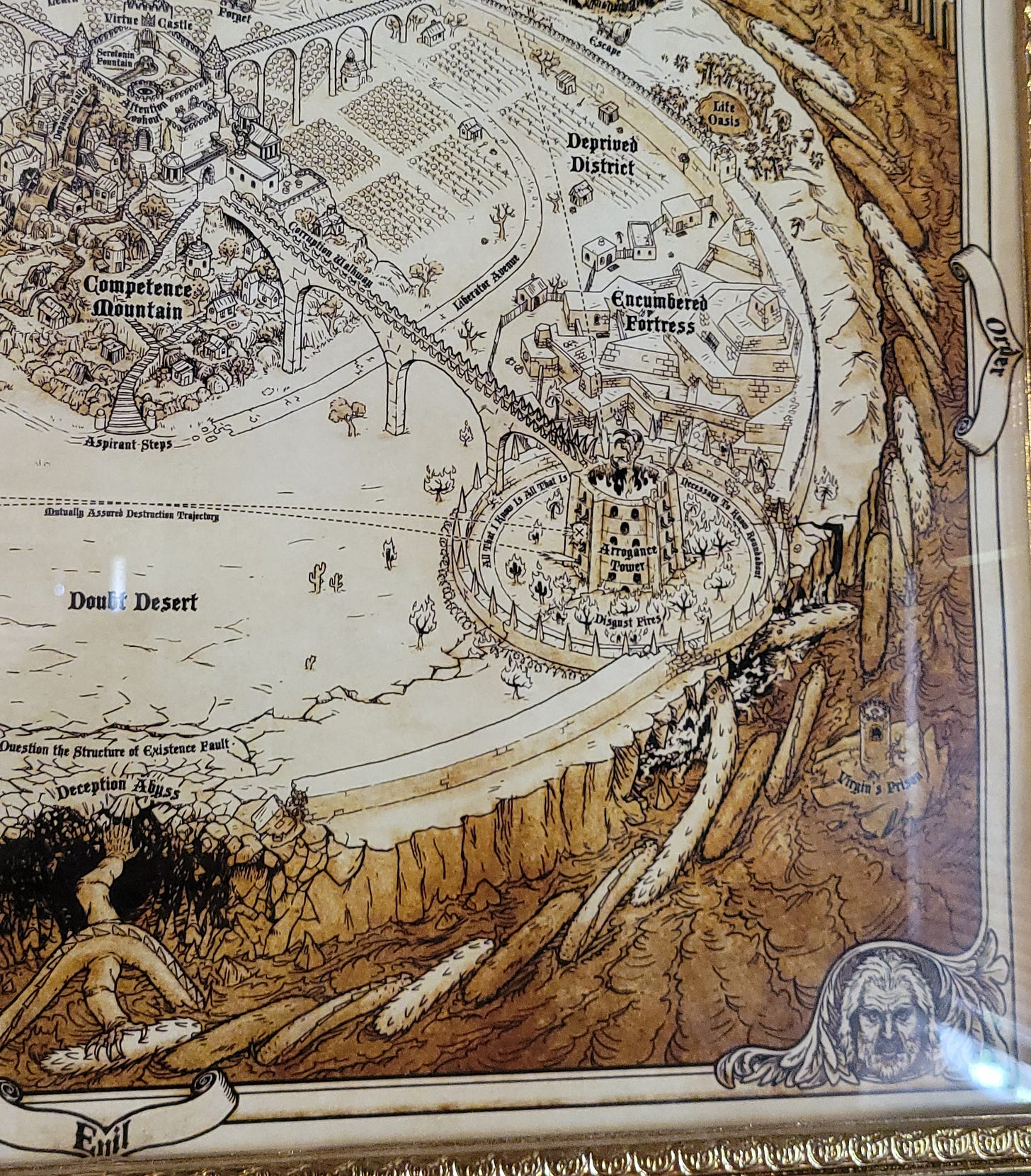

To return to the point: When an individual departs from the morals set by their society, that society departs from the individual to the extent that the society is orderly. A Paladin defends the people of a society (their “good” part), yes, but so too do they defend the very structure of their society (their “order” part) and the laws and order thereof. This is why a paladin’s struggle is so immense and painful when the society that he defends is systemically evil, hurting its own people. It is clear that order and good do not always go hand in hand: The hells in D&D are quite structured, even maximally so, yet they systemically inflict some of the greatest evils in the universe. Subverting such structure, be it within the hells or within heaven, is punishable to the highest degree. This is why places such as the Encumbered Fortress are narratively resonant.

Lying within the wall of society, the encumbered fortress locks itself into its traditions—its order for the sake of order. It safely rests, isolated from all others. Although it is partitioned off from the rest of society by its own feeble wall, the bulwarks of the fortress are inward facing, intended to maintain total control over those within. Naturally, it borders both the high tower of Arrogance (Babel), which boasts of its supreme ways (the negative trope of fundamentalism), and the deprived district, as the poor must be kept in their place as well. Those who escape this wall of society find just on the other side that nature does indeed provide sufficiently in the Life Oasis, yet it is precisely this portion of the border wall of culture that is thickest, with watchtowers present to ensure that the established order remains unbroken.

In this way, Order answers the question of personal being and agency: One must remain affixed in their place in society. There are no exceptions. No change is good.

Chaos, on the other hand, embraces all change as good. One’s destiny is entirely up to themselves, and the society must not interfere. Allowing one to determine their own fate, their own being, is a mandatory moral good. However, if one embraces this singular moral, the order of their ancestors—the morality passed down through society—is left in shambles; it becomes ruins to be combed through at their whimsy and peril.

In this way, a society may give its people more or less agency in their way of being in accordance with its degree of order or chaos, respectively. Neither of these paradigmatic answers both reaps the potential benefits of society and minimizes its potential oppression. Nevertheless, the paradigms help us to see that the answers that we seek may differ according to one’s society.

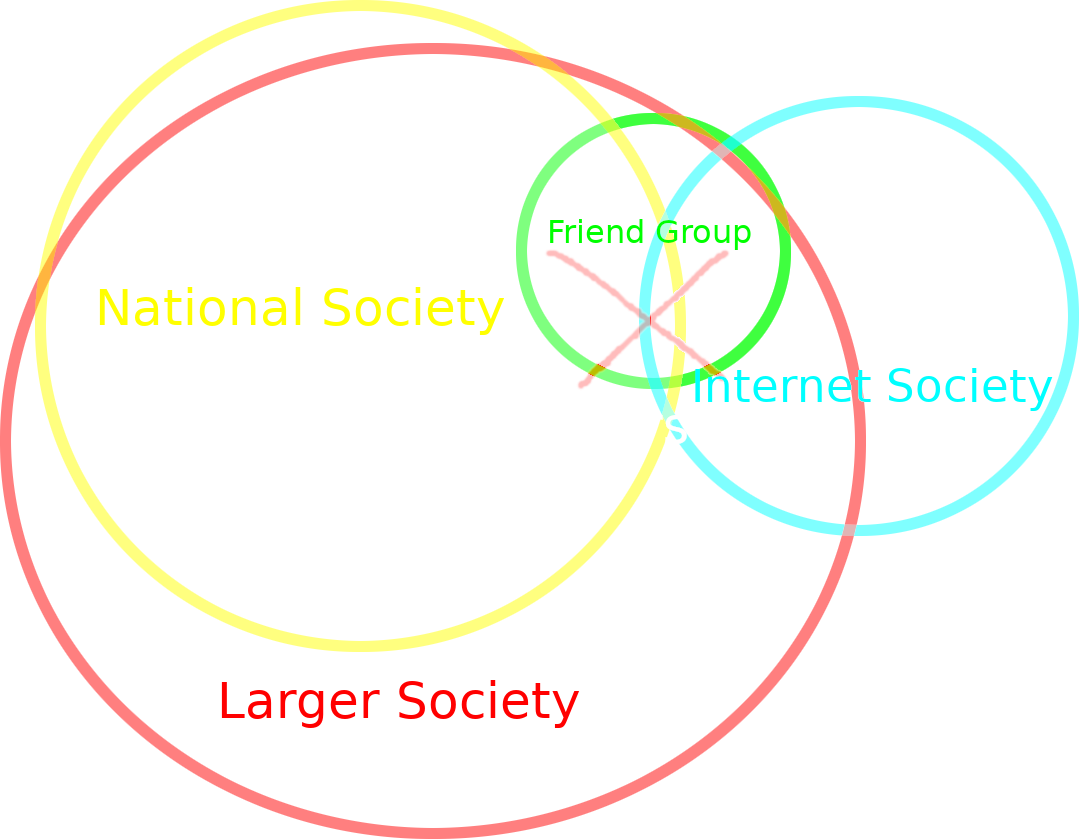

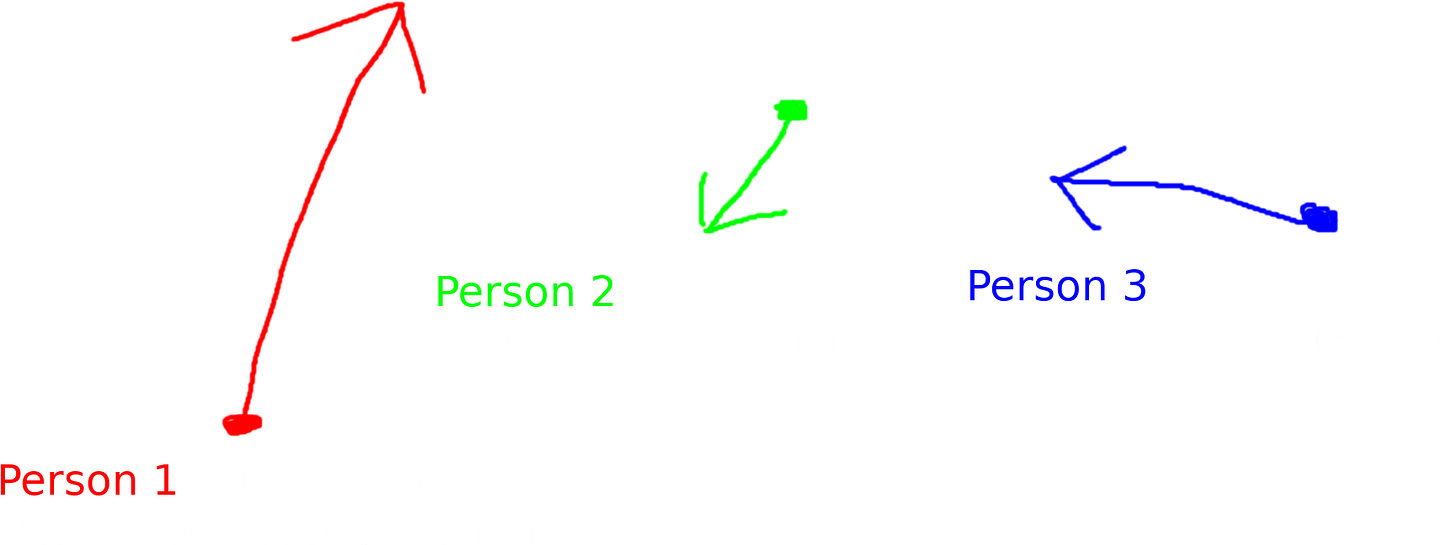

Up to this point, I have spoken of society in a typical way: as a monolithic construct that simply exists. While this is helpful for an initial definition, I find it more incisive to think through these ideas with a model of the societal landscape relative to an individual. The landscape itself is a theoretical multidimensional space representing the space of all possible societies. Each society has a position (its center point) and occupies space (in each of the dimensions of the landscape) in this landscape, while the individual is at the very center of the space. For viewing purposes, although not strictly accurate to the model, it may be helpful to measure the size of a society simply by the number of people therein. In this case, the distance from the center of the landscape (where the person is) to the center of a given society represents the difference between that person and the total norms of that society. One may participate in a physically very small society, such as a local book club that features symposium-style discussions on philosophical topics, yet that society may have a very rich and historically-steeped set of practices and thus function as a very important society within the individual’s societal landscape. In our little drawing, the individual would be very close to the center of that society.

In sum, in this model, a person’s position within the societal landscape represents the extent of moral influence that various societies have over that person. Indeed, while it may be useful to speak of “a person’s society” as a singular thing, that approach would equate to the following: taking the person’s proximity to the position of each of the societies in which they participate within their societal landscape as a measurement of the moral influence held by each of those societies over that person and summing the resultant set of moral influences on the individual to form a single influence—into the influence of “one society”, if you will. In contrast, my model allows for, among other things, notions of competing societal forces across one’s moral landscape.

Now, we return to the question at hand: “To what extent is it possible, practical, and good for one to reject this gift [of moral guidance]?” Naturally, the answer is, “It depends”. The archetypal positions are probably too extreme in any case. More importantly, we haven’t really grounded the question yet, so we don’t even have a path towards an answer. Furthermore, we’re actually begging the question by invoking the notion of “good” twice within the question, implying that there may be a greater moral good than that which the society offers. These problems threaten to place this essay in eternal draft purgatory.

Nevertheless, perhaps there is yet one path forward via the introduction of the belief that there actually is a greater moral good than that which the society offers. On this point, even if on nothing else, I expect Christians to readily agree.

Indeed, it depends: It all depends on what your aim is. To invoke a similar model, but one quite distinct from the one I’ve just outlined for societies, humans can be thought of as vectors in the space of all being; vectors that are necessarily progressing through time. A person’s being at a given moment is their position. Their being, however, also has a becoming—the direction in which the vector is aiming within the space of all being. This becoming has a particular maximum magnitude: the distance that it may travel in the becoming direction during a given period of time. We might call this magnitude a person’s agency.3

But what are the real dimensions of a human being? What are we really pointed at? What do we aim for? It is interesting to think that we may aim without perceiving the ultimate target of our aim. Aim is merely a direction within the space of all being, and our occupation is limited to a point: Our being necessarily does not comprehend the whole of this space. What we can comprehend, however, is the being of another person. We can sense their direction, perhaps not in full, but enough to aim at them—at their being. Our stories, our morals, our ideals, indeed, all of our directionality in life is tied up with becoming someone. To try to aim at anything other than another being is incoherent: We cannot aim outside of the space in which we are defined. Still, this notion of aiming is flexible: the person at which one aims may or may not actually be a different real person—it may simply be an image of oneself with some variations, or an idea of a person as communicated through some narrative.4 Indeed, it is the very space of all being in which we operate; any point within this space represents a specific variation of being that is theoretically, albeit not actually, attainable by any person.

So, who is your aim? Who are you aiming to become? Without mixing our metaphors and models, we can ask: How does who you want to become relate to the societies of which you are a part? Are the morals that they set appropriate for the person you want to become, or are they incompatible? Now we’ve found questions that may actually have answers!

It may not be possible for you to reject all of your societally gifted morals, nor may it be practical or good for you to do so.5 Possibility is limited by reality. Practicality is limited by one’s agency. Goodness is… well, without an answer to this, we’re simply encouraging radical individualistic morality—back to chaos again! It is good for you to follow your vector! To grow in magnitude/agency! Ah, see, that’s just the thing: We’ve already implied that there actually is a right answer to the question, “Who should you become?”—there is a higher moral good, a moral fact to ground all moral facts.

The answer is Jesus.

Order is good—society is good—to the extent that it gifts the morals of Jesus and increases the agency towards Christlikeness of those who participate in it. These are two distinct conditions. Any order or society is evil to the degree that it does not fulfill these conditions. When an order or society gifts morals that, when practiced by an individual, distance that individual from Christlikeness, that order or society is worse than chaos. Chaos, at least, is value-neutral, c.p.,6 whereas order is value-giving, one way or the other, to the extent that it gifts “morals”. Chaos orients individuals in random directions, while structure points them strongly towards someone, be that individual good or evil.

Consider church in these frameworks. Certainly, for Christians, the local church should occupy a central place in the societal landscape—even the very center! Moreover, religious societies may be both very large physically and very deep in history. The gifts of morality handed down by them are incredibly imposing: Potentially overshadowing all others in one’s societal landscape. Surely these morals would be good—we’re talking about church after all!

Sure, that’s probably the case. More good than evil, surely…

Well, I don’t know about your local churches, but it is easy to criticize mine. The low-hanging fruit generally includes things like social-club mentalities, celebrity-leader worship, catering (literally and metaphorically) for affluent members, a failure to mention discipleship in the church in any way, a lack of leadership and visible Christian living among overseers, blatant disregard for time-honored Biblical principles, an avoidance of certain types of discussions and over-emphasis of others, ignoring local orphans and widows, treating performative practices as sufficient practices, measuring success by worldly standards, prioritizing building projects over human needs, theological echo chambers, socio-cultural echo chambers, superficial community engagement aimed at congregation growth, political partisanship disguised as faith, an unwillingness to address historical wrongs, prosperity-focused messaging, and institutional self-preservation—additionally, why not while we’re at it, we could mention dramatic failures of pastoral infidelity, abuse of members, outright fraud, and practices aimed to maximize wealth in spite of “not for profit” status.7

In my previous post on this topic, I noted that a local church is an assembly of those who follow Christ. I also argued that our local churches qualify as “social institutions” and that this fact is a problem. To connect some dots between these ideas, we need to link societies to social institutions, and, ideally, understand some mechanism therein that underlies how societies “gift” morals.

Let’s begin by pointing out that society is very complicated. I mentioned the “space of all possible societies” before, and I intentionally left this fully vague. I have no idea what the dimensions really are. As I’ve noted before, I am relatively unacquainted with sociology. However, I understand that social institutions are a part of a society—the specific part thereof depends on what theory of social institutions you ascribe to, but they are at least some part. By some accounts, societies actually are systems of social institutions.8 By other accounts, social institutions establish morals within societies.9 Now, these may be quite bold claims: On the one hand, we have a view focused solely on the holistic account of social institutions, and on the other, we have a morally-focused teleological account of social institutions. I’m not sure what to make of all of this, except that it seems likely that social institutions are somehow mechanistically involved in the society’s setting of morals. Let’s dive in a bit deeper into social institutions, seeking a more specific mechanism for how societies set morals via social institutions.

In a footnote within my previous post, I mentioned that social institutions have constituent properties, including structure, function, culture, and sanctions.10 Examining each of these in turn may reveal some morally formative mechanism.

Structure, no-doubt, is a significant part of “order”, as discussed above.

Function is probably something related to the society to which the social institution belongs: the purpose of that social institution relative to that society.

Culture… oh, there’s that word again.

And sanctions: a mechanism of enforcement and self-preservation for the social institution.

While structure may carry inherent/implied morals within its organization, function specifies and highlights an aim that is inherently a moral statement, and sanctions more explicitly deal with the negative side of morals—what is bad to do—it is culture that most directly deals with morals, as far as I can tell.

Culture is one of the two or three most complicated words in the English language. (Raymond Williams, Keywords: A Vocabulary of of Culture and Society, p. 87.)

So, the situation I want to suggest is this: within society, we have social institutions; within social institutions, we have culture; and through culture, morals are established, spread, and otherwise gifted by the broader society. Culture may be present in places other than social institutions as well: Household culture, friend-group culture, hobby–niche culture, driving culture, “nerdom” culture, grocery store culture, and so on and so forth. Given my hypothesis that our local churches are social institutions, we can derive that local churches would have cultures, but those cultures are not necessarily of the church as such; however, they may be of the social institution of the church. Churches may have cultures of their own that are distinct from that of the church as a social institution to whatever degree, especially given our model of the societal landscape (or, perhaps an analogous model we might call the cultural landscape), yet we then must wonder: In what culture(s) is one participating when acting out the actual activities of the church service? When one listens to a sermon, is the culture of the social institution at work? When one sings, prompted by the worship leaders, is this a church culture thing, an institutional culture thing, or both simultaneously to some degree? How can we differentiate among these things? What is the true, experienced, and affective culture of a local church?11

This is a difficult question to unravel. However, consider this: Where in the structure of the church as social institution is the pastor? Where are the worship leaders? To the extent that these individuals occupy “high” positions as recognized by the church’s culture—and I would argue that they typically occupy some of the highest positions—they themselves are the aim; they are the persons that participants in the social institution see as “good”. The culture of the church as social institution points to these individuals as “high and mighty” as the very structure of hierarchical social institutions suggests;12 their roles are literally higher in the organizational hierarchy. These individuals, by virtue of their elevated position in the church's social structure, become the implicit moral exemplars of the congregation. The culture recognizes and reinforces their authority, creating a hierarchy that shapes how members understand Christianity itself.

It is easy to visualize the structure of a church as social institution: Look at the roles and positions that are formal (and perhaps informal), and see who occupies them. We have job titles associated with many of these and volunteer titles for others. Individuals who are in these roles have different aims according to their roles, and supplicants within the social institution may variously aim at the people in these roles, seeking to join or even displace them.

Contrast this with the New Testament model: We do have overseers who are to lead primarily by Christlike example, and we do have deacons who are to be exemplars of Christlike service; however, every member of the church is called to occupy the exact same role: that of emulating Christ, that of the body of Christ, and that of being unified in Christ. This entails being in the imago Dei, wholly following Christ, who is the fully human-fully God Imago Dei. Within this unity in His body, a diversity of gifts may be practiced, including those of service and leadership, yet we must not fool ourselves into thinking that we are to follow anyone other than Christ, no matter how cool our flesh may think their gifts are. To do so is to apply worldly standards to the church. “Overseer” and “Deacon” may be named “offices”, yet this minimal effective hierarchy is not the same as hierarchies of social institutions. Whereas the hierarchies of social institutions represent the various positions which one may occupy, each with their own aim and as aims unto themselves, the positions within the hierarchy of the church are prototyped à la Christ Himself, each and every one equally called to the same aim and holding the same exact position relative to Him, the true Head. Rather than “positions”, we occupy ourselves in the body, the beneficent differentiation in our beings accomplishing the mission of the Church: Together we can be Christ as the Church.

In this way, I suggest that the true culture of a local church can be discerned by examining its culturally recognized structure. Does this structure reflect the New Testament model, or does it reinforce a typical worldly position-centric hierarchical model?

When the church's culture primarily orients believers toward human leaders rather than toward Christ himself, it subtly redirects our spiritual formation. Even when the content of preaching and worship explicitly points to Christ, the cultural dynamics can overshadow this message by reinforcing human authority structures.

I’ve commented a couple of times now on the oddness of the ubiquity of preaching and worship (specifically the more performative, music-based worship prevalent in evangelical churches) in our modern churches: Why are these two elements and not others present in the vast majority of so-called churches of all denominations and traditions in North America? I think one answer is that these two elements are particularly effective at cultural propagation—indeed, they are means used to further the morals of the society via social institutions. Through worship, our inner being is shaped, our emotions are affected, and our desires are shifted—hopefully towards Christ. Through preaching, our minds are guided along specific paths, our imagination is exercised, and our agency grows—hopefully to pursue Christ. The centrality of these activities becomes explained and obvious in this light: These activities most directly address the two critical elements of being and becoming (the position and direction of humans as vectors). Indeed, they most effectively cause what is sometimes referred to as "moral formation". So, this explains the purpose of these activities, but who is driving the need for moral formation? Perhaps it is simply: The culture. The culture of the church as social institution would naturally seek moral formation in its members in order to strengthen its identity relative to those of all other churches as social institutions, thereby vying for partisanship as a means of self-perpetuation. “We” are the right ones; “they” are not as pure. Indeed, this motivation for moral formation would be very different from one born out of the perspective of a new testament church.

With this in mind, in what direction would one’s being move if they followed this moral formation? Would it move towards Christ, or would it move towards some ideal person in the context of the social institution?

I would like to try to sum up this portion of the argument like so: To the degree that the people who lead the preaching and worship within a church are viewed by the church’s culture through the lens of their position within the social institution (rather than their position relative to Christ), the preaching and worship of that church are morally formative towards the social institution (rather than towards Christ). Following the morals formed through preaching and worship may also move one towards Christlikeness, but it is difficult to see how this may be accomplished in a culture that recognizes the people leading the preaching and worship of the church as occupying higher roles than one’s own. This is because, as I’ve already posited, participants in a social institution necessarily aim at the leaders of their social institution; those leaders represent exemplary being in that institution. This systemic feature is doubly pernicious when the individual being aimed at claims to represent Christ—a claim at least implied by those in high positions in the church as social institution. If this claim is believed, the supplicants in the social institution will have a warped view of Christ, viewing Him relative to the aimed-at person in the social institution rather than directly as Head of the Church. This is the culturally-recognized structure of the church as social institution replacing of the New Testament vision of the church.

Accordingly, it is a major disruption when these leaders fail the morals attendant to their position. Such a disruption ripples through the members of the social institution, and it may be grounds for replacing that individual.13 How are these morals made to be attendant to a position in the social institution in the first place? Positions may have “moral expectations”, and there may even be sanctions against breaches thereof, yet it is the culture that truly enforces these morals and sanctions. Indeed, the people who are upset by breaches of these morals are the ultimate adjudicators thereof: The members of the social institution who are in good standing constitute the social institution’s culture. In this, we see once again the culture of a social institution at work towards moral formation. It is the culture that punishes and rewards. This is true not just for leaders but also, to a lesser degree, for any person in the social institution.

So far, I’ve focused on two cultural mechanisms for moral formation: That of looking to leaders as moral exemplars and that of the primary activities of local churches, namely preaching and worship. There are, assuredly, many other methods (for example, those I suggested for the structure, function, and sanctions of social institutions). I’ve also provided a tentative method for identifying what culture(s) are present (or perhaps for identifying the dominant culture) in a local church: Observe the socially recognized structure of the local church and see if it aligns more with structures typical of social institutions or more with the structure forwarded by the New Testament. These ideas largely satisfy my goal of exploring how churches as social institutions are related to societies, and how morals are formed through the cultures of churches as social institutions. In these ways, I argue that the culture of the social institution of the church is majorly at play through the primary activities of the church, and that those activities are aimed at moral formation that is beneficial to the social institution of the church rather than strictly towards Christ.

This conclusion compounds the suggested conclusion of my previous paper: The Scriptures do indeed provide a much more adequate answer for moral formation that is truly unto Christlikeness than our churches as social institutions do. The solution I propose is the same as before: Focus on only the model given to us in the New Testament. Do just that, and do not go beyond what is written.

More importantly, as a major academic topic, these ideas related to morality are explored much more adroitly elsewhere than I could ever do. Due to the nature of this post, I broach several such topics, inadequately explore them, and move on, attempting to make some sort of cohesive quest towards exploring the question in the introductory paragraph. I suppose when framed as such, it’s not all that unusual, and this footnote is unwarranted.

Technically, in this context, “Patriarch” refers to a title that clerics receive at level 10. It is at that point that they are effectively able to found their own order, or rather, their “stronghold”. We’re going to stretch the strict meaning into a broader narrative motif to make a point in the main text.

It is possible for a person to have already nearly reached the being at which they aim and still to have high agency. This can’t be represented accurately in this image, but the model itself would have no problem handling this case.

Even if one is aiming at a different version of themselves, they are still aiming at the idea of that person in their imagination—that is, the same structure applies if your person–aim is self-referential.

We’ve accidentally skipped over a critical clarifying question: How are morals and being connected? It’s easy to pass over this issue, but our models would certainly be disconnected if we failed to address it. We’ve discussed morals in a definitional sense as “norms and patterns that govern our actions”—morals may be acted upon such that they are followed or allowed to govern one’s being. Given sufficient agency, actions may be taken that bring one’s being into accordance with the moral. This is exactly the driver of one’s movement in the space of all possible being.

It is worth considering an odd case (per the models): because one’s societal landscape is personal and the distance between individuals and Christlikeness on different dimensions of being vary across individuals, certain societies’ moral gifts may be better than chaos for some people who are further from Christ while being worse than chaos for people who are closer to Christ. That is, the relative benefit (movement towards Christlikeness) of following some morals is different for different people.

As noted in the above charts, both good and evil may exist chaotically, but that goodness and that evil are not enacted through structural means. Societies need some amount of chaos—change— to be healthy, and chaotic-leaning societies may exist; however, chaos in a society is inherently societally destructive. The built-up wealth of culture that accumulates over time and strongly presents morals and values is not maintained, thereby eliminating the possibility of very strongly gifted morals. We might feel that morals in a chaotic society are very strongly gifted, but in the greater scheme of things, even those morals are quickly changed in a sufficiently chaotic society. The more chaotic a society is, the less likely the structures necessary for strongly presented morals are to exist.

No, I don’t feel better. I feel sick.

I hesitate to do the whole ‘search the internet for academic articles that prove your point and then just quote the abstract’ thing, but here we are anyways: I just don’t care about academic standards anymore.

“Aside from complexity measured in levels of political integration, societies as systems of social institutions have another fundamental characteristic that can be called a ‘basic principle of societal organization.’ The principle of organization a society embodies depends on the way its institutions are arranged with respect to one another.” Bondarenko, Dmitri. (2020). Social Institutions and Basic Principles of Societal Organization. No, I’m not even going to cite it correctly.

“Social institutions are the patterns that define and regulate the acceptable behavior of individuals within our society.” Baral, R. (2023). Exploring the Prominent Role of Social Institutions in Society. International Research Journal of MMC, 4(2), 68–74. https://doi.org/10.3126/irjmmc.v4i2.56015

Miller points to four constituent elements of social institutions: structure, function, culture, and sanctions. Miller, Seumas, “Social Institutions”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2024 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.), https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/social-institutions/.

If local churches were not social institutions, this would likely not be a question. The church culture would necessarily and simply be the church culture, sans some other sort of culture-inducing thing also overlaying it (I’m open to possibilities).

The idea that the structure of social institutions is hierarchical is a relatively typical view. As Miller suggests in his overview:

“Roughly speaking, an institution that is an organization or system of organizations consists (at least) of an embodied (occupied by human persons) structure of differentiated roles (Miller 2010; Ludwig 2017). (Naturally, many institutions also have have additional non-human components, e.g. buildings, raw materials.) These roles are defined in terms of tasks, and rules regulating the performance of those tasks. Moreover, there is a degree of interdependence among these roles, such that the performance of the constitutive tasks of one role cannot be undertaken, or cannot be undertaken except with great difficulty, unless the tasks constitutive of some other role or roles in the structure have been undertaken or are being undertaken. Further, these roles are often related to one another hierarchically, and hence involve different levels of status and degrees of authority.” Miller, Seumas, "Social Institutions", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2024 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.).

I believe this feature can be regularly found in churches as social institutions. I will admit that it is probably possible to have the hierarchical structure of a social institution without this culture of treating individuals in higher roles as “high and mighty”, but this is not what I have observed in any social institution. I believe the cause of this is psychological in nature.

This idea of replacement is natural in the context of positions within a social institution, but it is unintelligible in the context of the structure of a New Testament church, as members of the Church do not occupy roles but simply exist as parts of the body.

The vector metaphor is very helpful. It's as if Paul's, "follow me as I follow Christ" could be said don't follow me as a point, but follow my vector in so far as it is aimed at Christ. Aiming for paul (or anyone) as a point would actually lead a person infinitely away from Christ.